My great uncle Peter, the husband of my grandfather’s sister Thelma, was a large figure in my life. I rarely saw him out of his armchair at home due to the partial paralysis caused by polio from his time in the army, but he had a quiet intensity and passion which drew me in and sparked my curiosity as a child. He was a man of many hobbies, which he pursued with an openness and humility which belied his obvious talent for learning. He is one of the people in my life to whom I attribute my own inclination to try and try again to master new skills.

Towards the end of his life, Peter spent some time with a group of aspiring writers. Together they published several collections of writing, one of which I was recently given by my mother. I’m taking the time to digitise his writing here as a form of memorial, and as a reminder to myself of the way he inspired me to try new things with openness and passion.

My Life in the Army by Peter Foakes

I left school when I was fifteen, in 1949, and worked for a year as an office boy and junior auditor in Central London. However, I had always had an inclination to join the Army and see something of the world. So, I enlisted as a Boy Soldier when I was sixteen.

On a Saturday in November 1950, I made my way to Euston Station and thence by rail to Lichfield in Staffordshire, to the Regimental Depot. There were about a dozen of us Boy Soldiers, who mostly came from London and the Midlands. Discipline was strict and after a couple of weeks of Basic Training I was told I was to become a drummer. I was given a book called Elements of Music and was tested every few weeks on how much I had learned. I was also put under the tutelage of the senior percussionist of the Regimental Band.

In February 1951, the battalion was posted to Trieste, in what is now northern Italy. The important port of Trieste was occupied by the Germans until 1945, but was then claimed by both Yugoslavia and Italy. Our purpose, together with the Americans, was to act as a military buffer between the two countries until ownership was sorted out.

I was excited about the prospect of going abroad. After all, this was what I had joined the Army for, and the furthest I had travelled before enlisting was to Southend-on-Sea in Essex! Even though I was crammed in with hundreds of other soldiers, I enjoyed the journey abroad. First there was the troopship from Harwich to the Hook of Holland. Then the overnight train journey across Holland, Germany, Austria, and Northern Italy to Trieste. Finally, we were taken by lorry up to our positions on the Yugoslav border, by the Adriatic Sea.

I still remember the flat green Dutch landscape, split with dykes stretching away to the horizon. I vividly remember the black, ruined outlines of Cologne Cathedral, against the dark blue evening sky, and the toy-like castles on the banks of the Rhine. In Austria I remember the pristine countryside with immaculately painted houses. I also remember my first particular and exciting smell of Italy when we disembarked from the train.

We were stationed in Trieste for nearly two years. Soon after our arrival, I was able to begin playing with the Regimental Band. We played for all sorts of parades and concerts within the area. The Trieste Police Force also had a very good band and we used to take turns with them, playing concerts which were sometimes broadcast from the main Trieste Concert Hall. We were also able to supply two dance bands from within our ranks, which played for both civilian and military functions. The first time we played in the Trieste Officers’ Club, I was surprised to see the walls painted with German eagles and badges. Apparently, this used to be Gestapo HQ.

Sometimes we had to travel north through the mountains into Austria. To me, this was always an exciting journey. Great masses of rock, coloured blue-black, grey and ochre rose steeply from the side of the road, with occasional sights of bright green meadows. The mountain road could be quite dangerous in winter when it was covered in snow, ice or slush, and there might be a sheer drop of hundreds of feet on one side. But I also remember the sight of frozen waterfalls and large untouched areas of snow on the mountains. Summers were very pleasant in northern Italy and Austria. Sometimes we went swimming in the Adriatic.

There were occasional civil disturbances in Trieste because the population were mainly Italian and they wanted to ensure they became part of Italy. Apart from this, I enjoyed my time there. Finally our tour of duty came to an end and we returned to the UK to prepare to go to Korea.

We arrived at Pusan in South Korea in early 1953, after a five week sea journey by troopship from Southampton. We had sailed via the Bay of Biscay, and passed the lights of Gibraltar at night; then through the Mediterranean to Port Said, and down the Suez Canal and Red Sea to Aden. After this, we sailed via Colombo and Singapore before finally arriving at our destination.

We were allowed ashore for a few hours at Aden, which was very hot, dusty and barren outside the Port. Colombo was also very hot but busy and interesting, with friendly people. Singapore seemed to me to be very colonial with its Raffles Hotel, architecture and vegetation.

You could smell Korea from a mile off shore. This was because Korean farmers spread human excrement on their fields for fertiliser! Pusan is on the south coast and was crowded with refugees driven there by the war. They existed in ramshackle shelters around the outskirts of the Port.

Unfortunately, a couple of nights after we arrived, there was a bad fire in this area which resulted in numbers of refugees having nowhere to live at all. There were also many orphaned children who used to search rubbish dumps for anything to sell or eat. We all did what we could to feed them when we had the opportunity.

Our first duty was for two trumpeters and myself to play the ‘Last Post’ at a ceremony in the United Nations Cemetery in Pusan. This was to pay last respects to the dead from the battalion we were to relieve. At this time the Cemetery was simply a large area of yellow mud with a few tufts of grass here and there and large numbers of white painted wooden crosses. A group of Turkish soldiers were also present, doing the same thing for their dead.

Soon the battalion was ready to move up to the front-line. We, the bandsmen, stored away our musical instruments. We were to be on general duties and to act as stretcher bearers for the duration of hostilities.

We were moved by train from Pusan to Seoul. The city was full of United Nations troops – American, British, Canadian, Australian. Seoul had been captured by the North Koreans and Chinese and then recaptured by UN Forces more than once, and it showed. Parts of the city had been reduced to rubble by shell-fire. Our next move was made in lorries at night. We went up to the forward positions near the Imjin River and settled in.

At this late stage in the war, we were in static positions in bunkers and trenches, with tents further back. There was lots of patrolling by both sides and attempts by the North Koreans to gain ground with shelling and assaults on some parts of the Front. This went on until July 1953 when a truce was signed.

From then on, we were involved in peace-keeping duties. The band was re-formed and we were kept very busy performing all over South Korea and Japan, for UN functions and at civilian and military hospitals and camps. Our Bandmaster was eventually awarded the MBE for our efforts.

In September 1954, three of us young Bandsmen were sent back to the UK to receive a year’s course of instruction at the Royal Military School of Music, at Kneller Hall.

I very much enjoyed my time at Kneller Hall. The course commenced in October 1954 and from the start there was intensive training on our instruments and on music in general. In those days there were about 100 military musicians on the course from the UK and other parts of the world. During the summer months we gave weekly evening concerts on the bandstand which were well attended by the public.

Our main instructors were all working musicians. For example, the Senior Percussionist with the BBC Concert Orchestra was my instructor. He came once a week to teach and check on our progress.

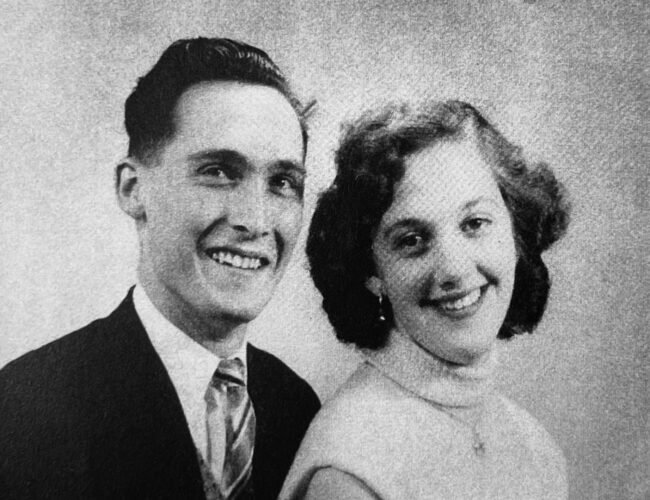

Early in 1955, I was lucky enough to meet Thelma, my future wife, at a ballroom dancing class in Richmond. I also got to know her family and was well looked after in my off-duty time. Thelma used to come to the weekly concerts as often as possible. The course at Kneller Hall came to an end in October 1955 so we had to report back to our Regimental Depot ready for our next posting, which was to Hong Kong.

Once again, we sailed to the Far East from Southampton and this time it took four weeks to get to Hong Kong. Our battalion was stationed in the so called “New Territories” near the Chinese border. We were brigaded with the Gurkhas and another British battalion to guard the border area. In those days, numbers of Chinese people from the Canton area tried to get over to Hong Kong to escape the Communist regime. Unfortunately, some were shot by the Chinese border guards in the attempt, but many others escaped and made a living in Hong Kong.

Kowloon and Hong Kong were quite exciting places to visit when we were off duty. There were plenty of interesting shops, cinemas and bars and the whole area was packed with people. In fact it was so crowded that some poor refugees were actually living between large buildings where there was suitable space. As a band, we were kept busy with parades, concerts and guard duties.

On a Saturday morning in early September 1956, the whole battalion had to go on a five mile cross-country run as part of normal training routine. I had been having flu-like symptoms for a couple of days previously but did not feel ill enough to report sick and miss the run.

After the run, the band had to go for a drill parade on the barrack square. After drilling for about an hour in the blazing sun, I collapsed and was taken to see the Medical Officer.

Then, I understand, all hell was let loose. The whole band was put in quarantine and I was taken to the Military Hospital in Kowloon. Polio was suspected and confirmed at the hospital. Polio is highly infectious for the first three weeks and I was immediately placed in isolation.

Two of my friends were also isolated with suspected symptoms. Luckily my friends were able to return to normal duties after the three week incubation period. However, I ended up paralysed from the chest down except for my left arm. After the first three weeks the hospital staff started me on a strict daily exercise routine. This continued until I was shipped home in January 1957. Even on the troopship the routine continued. In the UK I was in three different military hospitals and was finally sent to the RAF Combined Services Rehabilitation Unit in Chessington, for six months, after which I was discharged from the Army.

By this time, I was able to walk with sticks or crutches so I am extremely grateful to the medical staff who made me exercise so hard.